In the 2000s there was an unprecedented flowering of Orthodoxy in Russia. Millions of Russians flocked to churches in search of their identity, the meaning of life, and moral guidance. Of course, even then many were satisfied with the most primitive forms of religiosity (consecrate the house, light candles), but there were also those who sought to discover the beauty of Orthodoxy in its entirety.

This was greatly facilitated by the Internet, which made it possible to make Orthodox friends, ask questions on Internet forums, and download a huge amount of Orthodox literature.

“Orthodoxy with a Human Face” and Mission 1.0

Dawkins has a concept of a religious meme. So, at that time “Christianity with a human face”, as it was understood by the apostle of England — Metropolitan Anthony Surozhsky — found a great response among Russians.

Reading his books, we understood that the Russian Church is not about headscarves and self-abuse on every occasion, but about a personal relationship with God, who expects an open heart from man, not his money and rituals:

“Give me, son, your heart” (Proverbs 23.26).

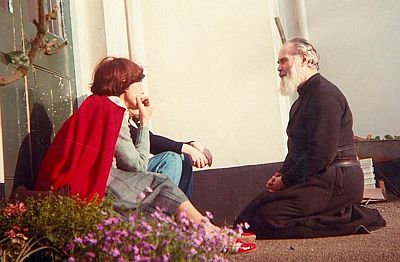

Anthony Surozhsky spoke sincerely, communicated with people on his knees, and slept on the floor so that a visiting sailor could rest on the bed.

Metropolitan Anthony taught that sometimes silent contemplation of the Image of Christ meant more than a ‘read out’ prayer rule from a book.

Such orthodoxy had little in common with clericalism, but at that time these dimensions of church life did not interfere with each other: everyone did what was closest to his heart. Some were silently earning church money, while others admired the Eucharistic theology of Fr Alexander Schmemann.

As a result, many of us came to believe that clericalism was an ‘endangered species,’ that the priest was a ‘friend of the Bridegroom’ who, when administering the Sacraments, contemplated in awe the mystery of the reunion of the human soul with the Lord.

In such ‘Easter Christianity’ each of us was called not to lament our wretchedness, no.

‘Enter into the joy of your Lord!’ — this is how many Orthodox saw the meaning of their lives.

In preaching the teachings of Christ, the proponents of this ‘Christianity with a human face’ endeavoured to make the faith of the new converts deep, mature and heartfelt. When communicating with such ‘men of the Church’, ‘outside’ people immediately realised that faith in Christ was serious. And that no human tricks, self-deception and magic tricks work here… Therefore, there is no point in ‘playing’ Orthodoxy with God.

This was humanistic orthodoxy.

We were taught that God Himself placed man at the centre of His attention, that man is valuable and significant to the Creator. What’s more! It turns out,

‘The Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give His life as a ransom for many’ (Mk 10.45).

This Christocentricity and humanity at the same time encouraged and discouraged many of us. Newly converted parishioners did not simply fall in love with such Orthodoxy, but sincerely wanted to share this experience with others.

So in the 2000s, a pleiad of missionaries (from Latin missio — commission, message) and catechists (from Greek κατήχησις — ‘instruction’, teaching the truths of the Orthodox faith and the order of church life) appeared in the Russian Church. They were all nuggets, not the result of training in special rhetoric courses.

They were ‘those who came from the great tribulation’ (Rev 7.14). Many had past experiences of seeking God in other denominations, some had had hard experiences of overcoming moral failures.

These people formed small fellowships, kept in touch on the Internet, and always shared their experiences, gathering annually in Moscow at the Christmas Readings:

‘How can we read the Gospel together?’, ‘How can we church children with special developmental needs?’, ‘What forms of work with youth can there be at the parish?’.

The difference between missionaries and catechists is very simple to understand: the former reach out to people who are far from the Church and sometimes even unbelievers. The missionary’s goal is to find common ground in communicating with people, to show the beauty of Christianity, and to try to destroy false stereotypes and fears about Orthodoxy.

As a result, churchgoers and people interested in religion felt that in Orthodoxy all dimensions of human personality are revealed and transformed:

— the Church does not call to switch off logic and intellect, because in Christ ‘the Light of Reason has shone in the world’;

— Church obedience is not disguised slavery and unpaid exploitation, but the ability to listen to and learn from the experience of others;

— prohibitions and restrictions are designed to train the willpower of Christians (‘hard in learning, easy in fighting!’);

— all church activity is subordinated to the main rule: ’love, and on the basis of this, do as you wish».

The missionary did not hurry to ‘drag’ a person into the temple, did not bribe him with sweet stories about paradise and did not threaten him with the torments of hell. He acted like the sun in Aesop’s famous parable about the traveller who wrapped himself in his cloak against the cold.

It is not for nothing that the Church people are compared to a dough in which the wheat kernels gave up their armour (hard shells) and became one — in the Church they do not feel aggression and do not need protective ‘complexes’ (they do not need to lie, conceal something or wear masks).

In the 2000s, missionaries sought first to win people’s love and then to spread the word.

Let’s call this the ‘Mission 1.0’ format

‘First love those to whom you want to tell about Christ, then make them love you, and then tell them about Christ’ (St Nicholas of Japan).

The goal of a missionary is to bring a person to the gates of the Church, to help them trust Christ and accept the Church’s view of life.

Believe me, in today’s world this is very hard work.

If a person looks at church life, or even if he is just curious, he has 100500 questions and doubts in his head like that five-year-old boy:

‘Why do priests drive Mercedes?’, ‘Why were scientists burned at the stake?’, ‘Is it true that Russia was baptised with fire and sword?’.

In order to respond intelligently to such challenges to the Church, a missionary must have the talents of a teacher, the patience of a physician, and encyclopedic knowledge in many areas. At a minimum, an Orthodox missionary must know the basics of biblical studies, Russian and ancient history, philosophy, and psychology.

The missionary is constantly accompanied by disappointments and failures, for there is no guarantee that his listeners will eventually become church people. And another important aspect of the problem: missionary work is in every sense a costly process, which is not fundamentally profitable. And if the rector of a particular parish aims at getting ‘short money’ (i.e. ‘here and now’), all this missionary work and youth ministry is like a bone in the throat for him. There are many problems, but no income. That is why for the last 30 years mission in the Russian Church has been carried out exclusively by enthusiasts with burning eyes, to whom the officialdom of the Church occasionally put sticks in the wheels, and at best condescendingly did not interfere, assigning all the laurels of missionary work to themselves.

If a believer has come to trust the Church, then his further ‘churching’ is the sphere of activity of catechists and priests. At this stage, there is its own pedagogical specifics, but in general it is the same hard work of many years of work with a living person (unlike selling candles and icons).

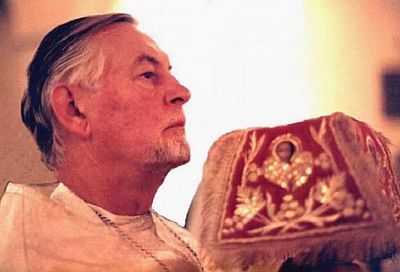

The significance of the personality of Kirill (Gundyaev)

It is important to note that before ascending to the patriarchal throne, Kirill (Gundyaev) positioned himself as a liberal missionary.

He hosted the programme ‘Word of the Shepherd’ and opposed the imposition of ‘costumed Orthodoxy’:

«we must learn to speak to today’s youth in a language that is understandable and accessible to them… there is nothing more dangerous for the cause of mission in youth than moralising and admonishing. A young person immediately associates this with lectures and reflexively rejects this kind of preaching.Young people who come to the Church should not be put into rigid restrictive frames: from now on they should dress this way and not that way, they should forget about fun and joy, they should give up sports, and they should not listen to secular music. By restraining the freedom of movement of newly arrived brothers and sisters, we not only commit unacceptable and unreasonable violence against their will, but also with our own hands we push away from the Church people who seek Christ’s Truth.

…By planting folkloric, museum, costumed Orthodoxy, it is as if we are signalling to society and the individual that our faith is supposedly irrelevant to modern life».

«I think that we have an interesting path to follow. It is important that this path should not be a path of parade reports about the events held, but that this path should first of all include real work with people at the level of parishes, schools, institutes, universities, colleges, vocational schools. In order for Christian youth work to be carried out at all these levels, we must have youth leaders who have the technology and know how to do this work. Work among young people must be interesting, because young people are dynamic, boredom immediately knocks a person out of balance».

At the time, Metropolitan Kirill stated that Orthodox mission was incompatible with threats and moralising:

«Does the Church not want to take the place of some kind of judge and tell people what is moral and what is immoral? Doesn’t it smell of clericalism, of attempts to occupy human consciousness and keep it in some kind of captivity? We answer: no. The Church does not assume the role of judge, the Church does not judge, but accepts confession and repentance. The Church is not a punitive institution, but a loving mother.

Let us dwell for a moment on the topic of ‘punitive institution’.

After the proclamation of religious freedom in Russia back in the early 1990s, new religious movements such as the ‘Unification Church’ (munites) and the ‘Mother of God Centre’ became active along with the emergence of foreign missionaries belonging to the world’s largest Christian denominations. Speakers of the Russian Orthodox Church already then realised the need to ‘counteract sects’, as a result of which in 1993 the ‘Information and Consultative Centre of St Iriney of Lyon’ was opened under the Department of Religious Education and Catechesis of the Russian Orthodox Church under the leadership of Alexander Dvorkin.

Under the pretext of protecting Russians from destructive cults and totalitarian sects, this organisation focused on persistent negative stereotypes and collected any negative information about the activities of the ROC’s competitors. All this caused serious criticism from representatives of traditional religious studies and experts in heresies. Roman Kon, Associate Professor of the Moscow Academy of Religious Studies, noted that the anti-cult approach is alien to the Orthodox tradition: theological, not criminal-psychological criticism is needed. The flaw in Dvorkin’s method was seen as favouring a legal strategy of ‘threats and compromising materials’ instead of theological analysis of doctrines, focusing on criminal charges and the international connections of various groups.

Dvorkin’s activities did not fit into the Mission 1.0 format, but in the 2000s little attention was paid to this, since sectarians were indeed considered dangerous, and prosecution of religious freethinkers did not actually come up at that time.

Our missionaries and catechists perceived such phenomena in the Orthodox environment as an inevitable evil at the Saviour’s Easter table. After all, even among the Twelve Apostles there was one traitor… If such a false missionary acts on behalf of the synodal structures of the Church, it is a ‘dark double of the Church’ (the image of Sergei Fudel).

Towards Mission 2.0

At one point it was Metropolitan Kirill (Gundyaev) who became the Russian bishop with whom missionaries and catechists began to associate their dreams of supporting and strengthening church outreach.

After his enthronement in 2010-2013, documents on mission and spiritual enlightenment were adopted, and parishes were obliged to employ staff responsible for youth work, mission and catechesis…

The change of leadership in key departments, the appointment of their own people (read — incompetent and extraneous) to the ‘staff’, bureaucratisation and the economic crisis in Russia — all these factors contributed to the removal and expulsion of former enthusiasts for the cause of mission and enlightenment.

The ‘good’ Metropolitan Kirill almost immediately turned into a ‘bad’ patriarch.

Having dusted the public’s eyes, he engaged exclusively in strengthening the vertical of power in the Russian Orthodox Church.

Already in 2014, it became clear that the patriarch’s liberal and missionary aspirations were in the distant past.

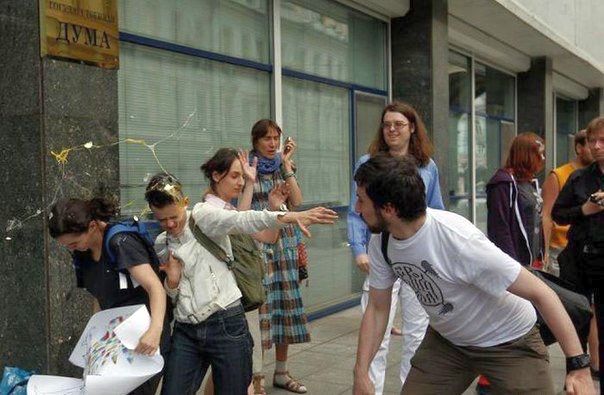

At that time, supporters of the Mission 2.0 format began to become more active. One of the most odious representatives of such a ‘mission’ was Dimitri Enteo (Tsorionov).

Starting in 2012, Enteo and a group of supporters regularly staged hooligan antics: they tore a T-shirt with an image that offended their religious feelings, or attacked an unauthorised procession of adherents of the pseudo-religion. Later, we heard about the disruption of a performance at the Chekhov Moscow Art Theatre, the beating of homosexuals and a pogrom at an exhibition of Vadim Sidur.

‘We prayed that God would help us use the media for PR,’ is Dimitri Enteo’s motto.

The activists of the ‘God’s Will’ movement had the support of three synodal departments of the Russian Orthodox Church, which was perceived by previous missionaries as the end of the era of ‘Orthodoxy with a human face’» and a return to the dark Middle Ages:

‘But this is your hour, and the power of darkness’ (Lk 22.53).

The mission of the persecuted and strong Church

The Church is in principle an authoritarian structure that does not tolerate any dissent. Already in the Gospel of Mark we read how Jesus ‘looked sternly at the leper (ἐμβριμησάμενος — growled from βριμάομαι — to anger) and pushed (ἐξέβαλεν — ’kicked him out‘) him away’ (Mk 1:43-45). The later books of the New Testament contain a similar exhortation for ordinary Christians:

‘’For such is the will of God that by doing right you may silence (φιμοῦν — to muzzle) the ignorance of foolish men’ (1 Pet 2.15).

In his letter to Titus, the apostle suggests that the Jews who deny the Messianic greatness of Jesus should be ‘shut up’:

‘For there are many rebellious men… who must be silenced (ἐπιστομίζειν — to muzzle)’ (Titus 1.10-11).

It appears that the apostles are urging Christians to ‘gag’ unchurched people.

What conclusion about the Church will these same unchurched people draw when they hear this magical ‘Shut up’?

The Church cries out for religious tolerance and the inadmissibility of violence in the religious sphere only under uncomfortable conditions. This was the case in times of persecution in the Roman Empire:

‘Every man,’ wrote Tertullian (3rd century), «has the natural right and authority to venerate what he recognises as worthy of worship. It is unreligious to force religious reverence on anyone. It must be rendered voluntarily, not in consequence of violence; for even sacrifices are demanded from a free disposition of mind» (Ad Scapul. 2).

‘There is no need to resort to violence,’ wrote Lactantius (3rd century), «because religion cannot be forced; to excite it voluntarily, one must act with words and not with blows… And if you think of defending religion by bloodshed, tortures, atrocities, you will not defend it, but will disgrace and insult it. For there is nothing in such a measure free (voluntary) as religion» (Instit. divin. V, 19).

After the recognition of the Church by the Roman state, the massacre of the Priscillianists followed as early as 385. This was the first time in history that people accused of apostasy from orthodoxy were executed by a secular authority.

We are witnessing similar processes at the beginning of the 21st century.

After the collapse of the USSR, the authorities in Russia were going through difficult times. Yeltsin was hardly re-elected as president. There were attempts to impeach him. At that time, the authorities were not concerned about the Russian Church, which was largely left to itself.

When the situation became more stable and predictable, the Russian Orthodox Church took its place in the general configuration of social forces and structures.

Why does it need a mission?

The Russian Church has monopoly access to television, schools and universities. All competitors of Orthodox Christianity have been shown the door (or a prison cell).

There are no miracles, so even Patriarch Kirill has changed. During Soviet times he was a liberal, but under the new conditions he has become a dictator.

Patriarch Kirill now relies on ‘violent treatment’, ‘punitive institutions’, and ‘the way of parade reports on the activities carried out’.

At his command, such ‘dangerous for the cause of mission methods as moralising and admonition’ have been planted among young people. For example, at the patriarch’s suggestion, schools began to teach the basics of Orthodox culture. Completely untrained teachers turn this course into a disgusting farce, but the patriarch insistently demanded that the course be made compulsory and taught in schools from 1st to 11th grade.

As Kirill (Gundyaev) predicted, ‘a young person immediately associates it with lectures and reflexively rejects this kind of preaching’. The patriarch’s pressure has further strengthened anti-church tendencies among young people. The number of atheists in Russia has recently doubled.

By 2025, representatives of Mission 1.0 had disappeared from the information field of the Russian Church.

Now ROC spokespersons authorise the beating of children, calling for ‘a woman to be broken against the knee, hacked off her horns… bend her, rub her, shove her into a washing machine’. ‘Women have become dead, cowardly and lecherous’ — news stories with such headlines have long been the norm. The number of taboos voiced during this decade is simply off the scale: ban hypermarkets from operating on weekends, ‘adult shops’ and much more.

Catechists and missionaries have long been dismissed. Priests customarily baptise and wed everyone in a row (which is uncanonical), and during the service they take thousands of pieces out of the prosphora, pronouncing the names of sinners unknown to them (which is completely untraditional).

As they contemplate what is happening, graduates of theological seminaries refuse to accept the sacred ministry. This is not the Church they came to and this is not the mission for which they studied in theological school.

Ordinary priests withdraw into themselves or abuse alcohol, seeing no way out of the situation.

The fixation on the topic of sexuality

‘Defending traditional moral values’ by Russian Orthodox Church speakers is an attempt to prove their importance and usefulness to society. Gradually, the focus of attention of the Church representatives began to shift towards abortion and special forms of sexuality, leaving the topics of social injustice or corruption out of the picture.

This option began to seem like a win-win situation: every second Russian is somehow connected with abortion, and sexuality is an extremely sensitive area for the formation of ‘own-stranger’ categories and guilt complexes in its adherents.

The propagandists of ‘family values’ lead a completely immoral lifestyle (sybaritism and same-sex sexual relations) and deliberately create a false image of the Russian Church as a bastion of traditional morality.

Not without the influence of Russian Orthodox Church speakers, sexuality has become one of the legitimate targets in the ‘witch-hunt’. Even masturbation, the guru of ‘Mission 2.0’, Fr Andrei Tkachev, attributed it to the problems of geopolitics:

‘war is going on because the seed pours wherever it goes.’

At the present stage, the leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church does not think about systematic work with people to attract new parishioners. Now some speakers of the Russian Orthodox Church simply hype with cheap and catchy meme content, while others attract media attention through low-brow swearing and scandals.

Mission 2.0 has won.