Let’s begin with mythology, which originally formed the worldview of ancient humans. Myths were a pre-scientific form of knowledge; other “forms” simply did not exist at that time.

‘Unusual Sexuality’ in Magical and Religious Contexts

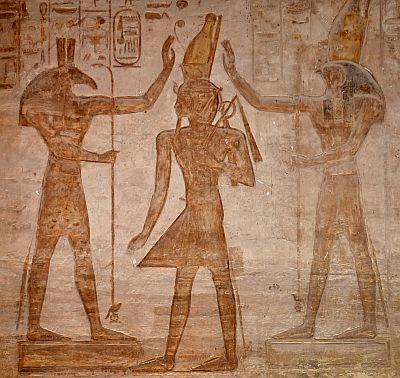

Let us look at the ambivalence (duality, contradiction) of gods in matters of sexuality. For ancient people this was no problem. Hermaphroditism occurred among divine attributes precisely as a paradigmatic expression of creative power. In other words, as a positive attribute.

For example, Zeus “gave birth” to Dionysus from his thigh and to Athena from his head. For humans this is impossible, but in the divine world everything is different.

The Egyptian creator god Atum-Ra self-generated — in one myth he emerged from his own semen by swallowing it and then spitting it out, producing a twin: Shu, god of air, and Tefnut, goddess of moisture, from whom all other gods descended. (This is narrated in the Pyramid Texts §1248.)

This highlights a difference between mythology and modern biology. In myths, semen is self-sufficient and the female body does not appear necessary.

In another version of the struggle between the Egyptian gods Horus and Set, Set proposes a sexual relationship to Horus.

According to the myth, the gods attempt to impregnate one another — which in a mythic context shows that in the world of pagan deities, taboos were freely transgressed and gender boundaries crossed.

There are many such examples. Among the Hittites, the myth of the castration of the supreme god shows even clearer references to sex between beings of the same gender. Kumarbi, the Hittite prototype of Cronus, bit off the genitals of the sky god Anu, swallowed part of the semen, and “gave birth” to the god of love from his hip.

In ancient Lybrande (Caria), the bearded Zeus was worshipped with “six breasts”. Regarding Dionysus, he was the most ambivalent of gods; in a fragment from Aeschylus someone who meets Dionysus exclaims, “Where do you come from, man-woman?” Appearing in both genders was not unusual.

Even among humans in antiquity there were ritual practices where men wore women’s clothing (and vice versa) to enact what we might call gender change. During rites dedicated to the Italic Hercules the Victor, both the statue of the god and the officiants wore women’s garments. The purpose of such ritual dress was not primarily sexual but symbolic — to return youth, obtain health, strength, or even immortality. These practices were connected to shamanic ideas where the mediator united male and female principles within himself to act in both realms.

In many ancient Near Eastern texts, cross-dressing appears in cultic or legal material. For instance, after the death of the Ugaritic hero Aqhat, his sister Pagatu dons male clothing in the absence of male relatives to fulfill the duty of blood vengeance.

Such depictions did not reflect prostitution or sexual identity as understood today, and they embodied symbolic or religious meaning. The environment that produced them was mythic and cultic, not scientific or moralistic.

Sexuality in the Jewish Bible

In contrast with mythological ambivalence and sexual symbolism, the Old Testament presents a fundamentally different framework.

The prohibition on certain sexual practices, such as the famous injunction in Leviticus 18:22 — “If a man lies with a man as with a woman, both have committed an abomination…” — appears in the context of religious and cultural boundaries set for Israel.

This prohibition is part of a larger set of rules aimed at distinguishing the people of Israel from surrounding nations and their cultic practices. What is labeled abominable in Deuteronomy 22:5 — “A woman shall not wear a man’s garment, nor shall a man put on a woman’s cloak…” — is for the Old Testament tied not to individual erotic preference but to covenant identity and separation from pagan rites.

Similarly, cultic prostitution is forbidden:

“No Israelite woman shall be a cult prostitute, nor shall any Israelite man be a cult prostitute” (Deuteronomy 23:17-18).

This stands against the fertility rituals that were widespread in many ancient religions and surrounded temple life.

It is clear that the God of Israel demanded absolute loyalty, and sex-related proscriptions were part of religious and cultural differentiation rather than a generalized moral condemnation of same-sex intimacy.

Interpretation and Context

There is no biblical terminology equivalent to modern concepts such as “sexual orientation” or “queerness”. These categories emerged only in the 19th and 20th centuries, long after the biblical texts were composed.

Homoerotic or gender-fluid behavior in mythologies elsewhere (such as Greek and Roman myths where gods like Zeus and Apollo had male lovers, and figures like Aphroditos embodied androgyny) reflects a worldview where sexual and gender expressions served symbolic, cosmological, or ritual functions, not personal identity.

The sacramental and symbolic nature of ancient rites shows that ancient conceptions of sex differ radically from the modern framing of LGBTQ identities. In mythologies, queer or unusual gender/sexual elements often pointed to power, creation, liminality, or divine ambivalence, not to a fixed category of personal identity.

Conclusion

In pagan religions extraordinary forms of sexuality were often seen as expressions of supernatural power or divine mystery, where crossing of gender boundaries or ritual dress was part of sacred enactment.

In contrast, the Old Testament reflects a period of religious confrontation, when sexual prohibitions served to separate Israel from the surrounding peoples and their cult practices.

The God of Israel’s demands for absolute fidelity and separation led to the formulation of prohibitions that framed certain acts as abominations, not because they corresponded to a modern sense of identity, but because they violated the covenant and threatened communal integrity.

Modern terms like queer or sexual orientation are anachronistic when applied to the ancient Near Eastern and biblical contexts; nonetheless, understanding how ancient cultures constructed and contested gender and sexuality enriches our reading of myths and sacred texts.

Aleksandr Usatov

ausatov@protonmail.com